Clearly Overthinking

Clarity matters. Connection matters.

Overthinking is how I search for both.

This blog is where the thinking meets the human.

Treating Psychological Safety as Safety Engineering

Psychological safety isn’t a feeling. It’s the absence of hazards. Treat it like safety engineering: find the risks, control them, and make work truly safe.

“I Know What We’re Going to Do Today” — Momentum, Focus, and the Joy of Getting Things Done

Every morning in Phineas and Ferb begins the same way: “Ferb, I know what we’re going to do today.”

It’s funny, but it’s also a perfect picture of something most of us spend our lives chasing — that clean, effortless leap from idea to action.

Neuroscience tells us why that spark feels rare.

When dopamine is steady, thought and motivation flow in tune; when it dips, plans fade and focus falls away.

But chemistry isn’t destiny.

We can design for it — through clarity, rhythm, and a touch of play.

We’re not going to build a rollercoaster every day.

We might never organise a global aglet-awareness event.

But some days, if we bring a little Phineas spark and a little Ferb steadiness to what’s in front of us — that’s a good day.

Listening Shapes the Brain

We don’t just hear music — we learn it.

Each rhythm and chord tests what the brain expects to happen next.

When the sound fits — or surprises us just enough — dopamine fires.

That pleasure is competitive plasticity in action: the brain strengthening whatever best explains experience.

The same rule shapes how we live and lead.

What we focus on grows stronger.

We’re always composing ourselves by what we choose to hear.

Why Fast Feedback Fuels Motivation

Progress feels good because it’s how the brain learns.

Every step forward — finishing a task, testing an idea, seeing a result — sends a pulse of dopamine. That pulse feels like pleasure. But the purpose isn’t pleasure. It’s feedback.

Dopamine is the brain’s teaching signal. It fires when outcomes are better or worse than expected, adjusting our confidence in what works. The spark of pleasure is simply the marker of a learning moment: “this path is working — keep going.”

This is why visible progress matters so much in our work, our teams, and our lives.

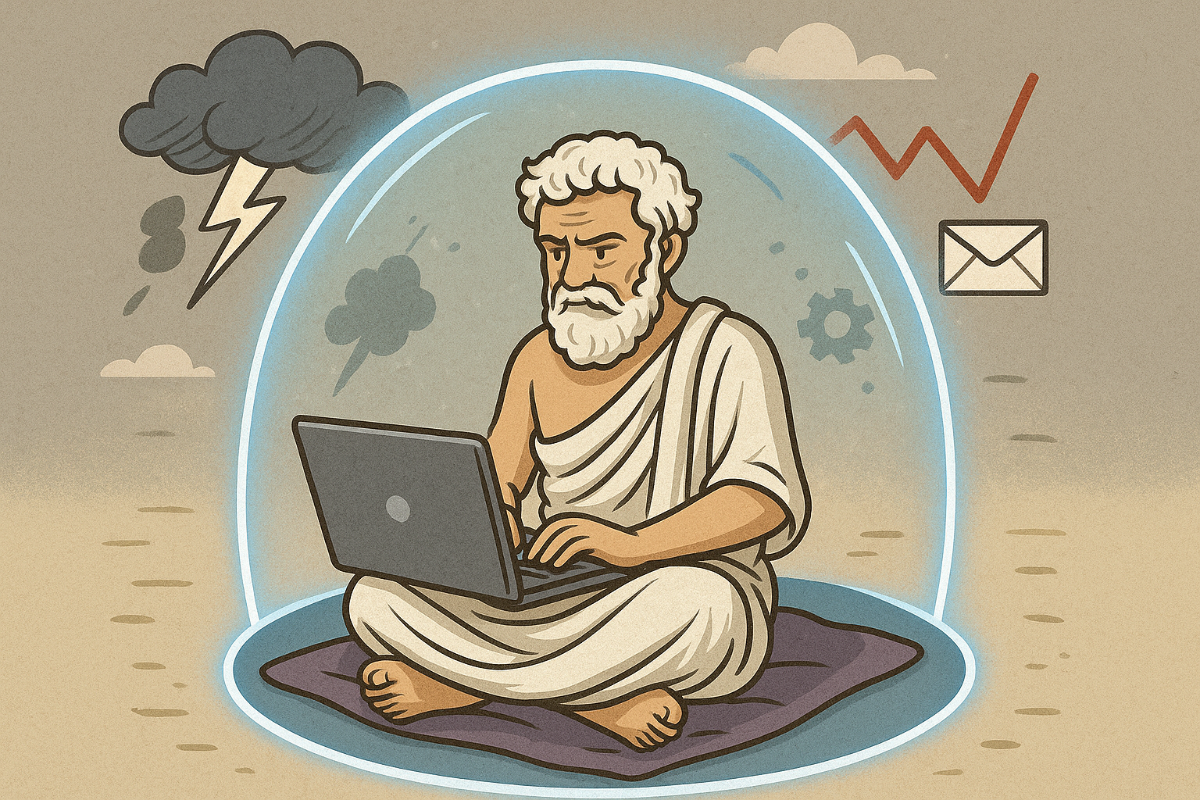

Epictetus, the Markov Blanket, and the Art of Clean Boundaries

“Some things are in our control and others not.”

Epictetus wrote that nearly two thousand years ago. Born a slave in the Roman Empire, he knew this boundary not as abstraction but as survival. His body, labour, even movement belonged to others, yet he insisted that freedom remained: not in events, but in how he chose to respond.

That single insight—the line between what we govern and what we cannot—is the heart of Stoic practice.

See the line. Act inside it. Release the rest.

Corporate Life: The Wrong Habitat for Human Brains

We did not evolve for cubicles, contracts, or conference calls.

Our nervous system was tuned by the firelight: thirty to a hundred familiar faces, leadership that shifted with circumstance, belonging as survival. Safety meant the freedom to speak, argue, and contribute without fear of exile.

That was our natural habitat.

Today most of us live in another. Offices, factory floors, and Zoom grids. Hundreds or thousands of strangers. Leadership fixed in titles and reporting lines. Evaluation became formal and impersonal. Our livelihood tied to people who may barely know us.

It’s a habitat our brains struggle to recognise.

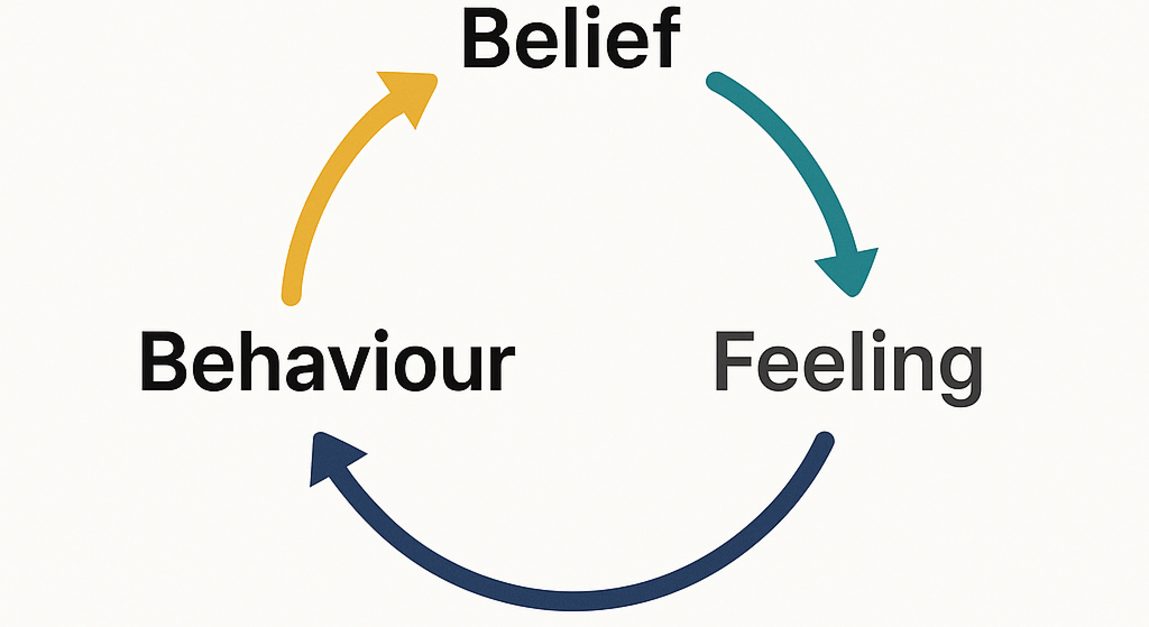

Beliefs Don’t Just Fit the Facts — They Fit the Feeling

We often think beliefs are based on evidence. In reality, they’re shaped just as much by feeling. Beliefs, feelings, and behaviours form self-sustaining loops — helpful at times, but limiting when they trap us. The good news? Loops can change. With the right conditions, old beliefs loosen and new ones take root.

The Cost of the Life Unlived

Every choice we make has a cost.

Economists call it opportunity cost — the value of the path not taken.

We usually measure that in money or time. But the deeper cost is harder to see: the life we didn’t live.

Life as Prediction

We often imagine ourselves as reacting to the world — responding to events as they happen. But the brain works differently. It doesn’t wait for reality to arrive. It is constantly guessing what will happen next and preparing us to meet it.

We are prediction machines.